You can hear the The Jade Market in Mandalay before you see it.

The roar of mopeds giving way to high-pitched whining of electric saws and busy chatter indicates you are near the Mahar Aung Myay Market, more commonly referred to as 'The Jade Market'.

The first glimpses of the rock which is revered throughout the globe (but particularly in Asia) occur outside the entrance to the market, where boulders of jade are being unloaded from trucks. The men are wearing the traditional Burmese longyi, a 2m length of cloth tied at the waist, and flip flops. Most of these boulders will have arrived from Kachin State, in the far northern reaches of Myanmar where much of the world’s jade is mined.

The boulders are then taken into workshops equipped with large electric saws which are cooled by water channelled from hoses fixed to the sides.

Once sawn, and having revealed colours from opaque white (known as ‘mutton fat’) through to translucent rich greens (known as ‘imperial’ jade and the most highly prized), the decision is made as to whether they will be made into carvings or further reduced into smaller slices for bangles or even smaller cabochons to be set into jewellery.

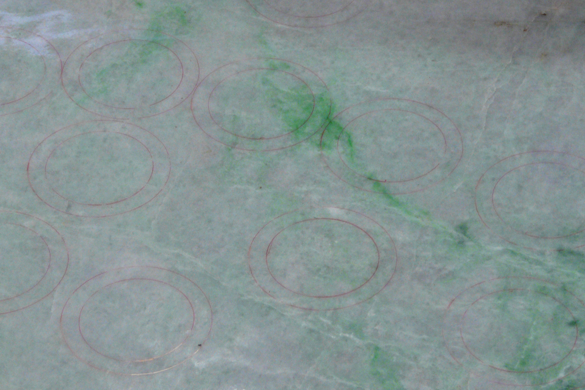

Amongst the workshops littered with sawn boulders, multiple blocks marked out with bangle templates were evident and given the importance ascribed to this particular type of jewel by the Chinese, for cultural, spiritual and medicinal reasons, that is no surprise. Diamonds are of no importance in this place.

There were areas where the cutters, kept company by one of the many local strays, were polishing the sawn faces of the jade boulders with small cubes of jade. Jade is microcrystalline and they seemed to be using those properties to achieve a good finish.

Getting nearer to the entrance, rows of lapidaries (stone cutters) power their laps (wheels) manually, rhythmically pedalling and balancing the cabochons on the ends of their fingers. Their skill is such that they create a highly polished, perfectly shaped dome by deftly tilting their fingertip and moving the jade against the wheel. Traders wander, examining polished stones in gem papers whilst negotiating prices. Symbols of the nation’s Buddhist beliefs are in evidence and everything, inanimate or not, is covered with a fine dust.

Those working on the more sophisticated electric wheels protect themselves and others from the spray of dirty water by using old tyres as guards. Nothing is wasted in a country which has been, until recently, cut off from the rest of the world.

Those giving more consideration to their fingertips somethimes use ‘dop sticks’ to hold the jade cabochons against the wheels, or a dop stick in one hand and a cabochon jade on the end of a finger of the other hand.

Others seem to prefer a more traditional polishing surface, using bamboo rods rather than wheels. It is hot, and the haze and aroma of the cheroots fill the air as we are proudly shown the intense green cabochons.

Inside the market, the pace does not reduce. We were the only Europeans in evidence with most foreign visitors (and the serious buyers) being Chinese. Those in the know don’t approach the stone traders but sit at one of the many tables furnished with a plastic stool and…wait. The traders will move from table to table showing their parcels of stones, stopping when someone expresses interest.

The buyers match up sets of stones and check the jade’s translucency and texture (how obvious the microcrystalline structure is) with their torches and then negotiations around price begin. Some discussions reveal there were no bargains to be had, and in many respects I was pleased by this. I’m not a believer that the people at source do not benefit from their natural resources or labours.

Nonetheless, this is a place that carries financial risk, there can be treatments applied to jade and it does take specialist knowledge to spot them. Buyer beware.

In places, the frenetic pace is punctuated by the sound of jeweller’s hammers and files in one of the many workshops where craftsmen are setting cut stones.

It’s not all work though, I was interested to see there are options for the traders and lapidaries to relax, with games tables and teashops. Refreshment hawkers weave through the crowds offering fruit or betel nut parcels to chew. Dodging the splashes of red liquid where the betel juice has been expelled at high velocity is a skill learnt quickly here, though communal buckets are provided to try and contain the issue.

I’m sure there are many significant deals being done out of sight, but even so, this was a truly fascinating insight into an aspect of the jewellery world and an opportunity to see pieces that will never find their way into the European market but are solely destined for Chinese buyers. A place that felt very ‘local’ to Myanmar is truly pan Asian.

Contact Clare to discuss bringing an international feel to your collection.